Karin Slaughter, welcome to this interview for Deckarhuset !

You write unusually violent and bloody stories, why?

I don’t think of them as unusually violent or bloody. My main focus as a writer is to use violence as a means of talking about greater issues affecting society such as domestic violence, child abuse and rape. I write about these matters in a frank and serious way because I think that readers want an understanding of not just what happens, but what happens next—as in, how does a woman who has suffered horrendous abuse put her life back together? How does a woman who has been raped manage to trust again. I delve deeply into the lives of my characters and their emotional responses to the sorts of crimes they see. The social aspects have always been my focus. I’m not interested in violence for violence’s sake.

Most of the really raw violence I have come across in novels are in stories written by men, why do you think that is?

I think that men have an easier time getting away with writing about violence. Mark Billingham and Jeff Deaver seldom get asked about the violence in their novels, but I think that both of these authors are very dark (and exceptionally good at what they do). On the other hand, women like Mo Hayder or Tess Gerritsen or I tend to get a lot of attention when we take on the same issues in the same way. People expect women to be softer, I suppose. The dichotomy is that in most countries, women buy the majority of the books. In the US and UK, for instance, almost 85% of all readers are women. So, we have always been interested in this subject matter. I think it’s about time we started not just writing about it, but bringing the perspective of women to the topic of violence.

It seems more and more common that authors use made up places instead of using

cities and places that really exist. Why is that?

I write two different series—one is set in fictional Grant County and the other is in Atlanta, which of course is a real town. I find it much easier to be in Grant because I can make up roads and neighborhoods. I’m always so nervous when I write about Atlanta, even though I’ve lived here more than half my life, because I’m sure I’ll get something wrong and some helpful reader will write a terse letter outlining my mistake. I find it much easier to be in a completely fictional world, as I’m sure most writers do!

Is there a difference in what kind of stories would work great in the US, contrary to what would suit the Asian or European readers?

I think that a good story is universal. I am, of course, grateful that I have extremely diligent translators for my work in various countries, but despite what Hollywood shows the world, there are more things Americans have in common with the rest of the world than things that set us apart. For instance, most Americans live in small towns. We don’t all inhabit New York and Los Angeles. Most Europeans live in small towns, too. I also think that as human beings, we all have a natural curiosity about violence. It’s in our DNA to note danger, whether we’re slowing down to look at a car accident or reading a gripping thriller late at night. Our brains are constantly learning from experiences, and there’s no safer way to experience a good thrill than in a well-crafted story.

Are you familiar with any of our Swedish crime authors?

Well, of course Stieg Larsson is well known here as well as Henning Mankell. Liza Marklund is absolutely fabulous and I eagerly await her next work. Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to get novels translated into English. The US and UK publish around 250,000 books each every year. There’s not a lot of room for other authors. I do enjoy many Scandinavian authors. Karin Fossum is an excellent storyteller and Peter Hoeg wrote one of my favorite stories.

How much of the time to produce a book is research and how much time is actual writing?

Usually it takes a year to complete a book, but I’m often doing research and making notes for two or three books at a time. Since I’m writing a series, there are some things that I think of about my characters that don’t quite fit in the current book but will work really well in the next. So, I’m always taking notes and marking articles that I think might be relevant to the next book.

You use really nasty crimes in your stories, why? Is it possibly to create a debate?

I think crime novels have always been at the center of debate because there is a certain immediacy inherent in the genre. Jim Burke wrote a wonderful novel (The Tin Roof Blowdown) about New Orleans after Katrina—it was angry and political and a damn good read; all the things that good crime novels are. He was able to write about a wound in America’s psyche that was still raw because he’s a good crime writer. He didn’t waste time staring at his belly button like so-called “literary” authors do. He sat down and wrote a story.

Not many authors write two “series” parallell, but you do. Is there an agenda behind this, or is it just for fun, to avoiv getting bored with your characters…?

I love writing, and I love taking chances with my work. When I wrote Triptych, it was because I had a story that wouldn’t quite work in Grant County. It opens with a prostitute being murdered, and we don’t really have those in Heartsdale—well, maybe we do, but no one really talks about them. I needed the anonymity of a big city, and Atlanta, my home, seemed like a good setting. Once I started writing about Will Trent, I couldn’t stop. I knew there were more stories to tell about him and so I decided there would be a second series.

Are there real people behind the characters in your stories?

I’m sure I’ve taken some people from my real life and put them in my books, but I’m never conscious of it. I think that every writer is a product of circumstance, so there is an eventual blending of real life and fiction.

How come you have written the books in the Grant County series in one order, but in hindsight I would have liked to read them in another?

I think that starting with Indelible is a good idea because it gives you a glimpse of things to come, and explains the genesis of Jeffrey and Sara’s relationship. Of course, as a reader, I am a stickler and I like to read everything in the order in which the author wrote, so perhaps there are people like me who, when they find a new author, start from the beginning and don’t stop until they’ve caught up.

A couple of your books have different names in different countries. This is nuisance when you travel a lot and buy most of your books at airports all over the world. Not only different covers, which is a hustle, but now different names? Why?

I leave the titles up to the individual countries. Generally the English versions all have the same title, but there have been two instances (with Skin Privilege/Beyond Reach and the upcoming Genesis/Undone) where because of market forces or another author having a book out already by the same title, we’ve had to change them. I’ve approved the title changes in both cases. Of course, in non-English countries they tend to change the titles more drastically. Since English is the only language I speak, I think it’s best to leave it to the experts!

What are you working on right now?

I’ve just finished Undone, the next book in Will Trent’s world, and I’m working on Broken, which takes us back to Grant County. A lot of things have changed over the course of the series and it’s been fun writing about Lena again.

If you were to suggest who we should interview next, who would this be, and what question would you ask this person if you could?

I would suggest Mo Hayder because she’s one of my favorite authors. What I would ask her is “Why aren’t you writing faster?” I’m dying for a good book from her.

By the way, did you change your last name, or is it a coincidence…

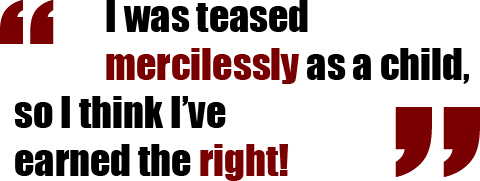

It’s a coincidence. I was teased mercilessly as a child, so I think I’ve earned the right!

/Many thanks for you time and see you at the Gothenburg Book Fair

Karin Slaughter, welcome to this interview for Deckarhuset !

You write unusually violent and bloody stories, why?

I don’t think of them as unusually violent or bloody. My main focus as a writer is to use violence as a means of talking about greater issues affecting society such as domestic violence, child abuse and rape. I write about these matters in a frank and serious way because I think that readers want an understanding of not just what happens, but what happens next—as in, how does a woman who has suffered horrendous abuse put her life back together? How does a woman who has been raped manage to trust again. I delve deeply into the lives of my characters and their emotional responses to the sorts of crimes they see. The social aspects have always been my focus. I’m not interested in violence for violence’s sake.

Most of the really raw violence I have come across in novels are in stories written by men, why do you think that is?

I think that men have an easier time getting away with writing about violence. Mark Billingham and Jeff Deaver seldom get asked about the violence in their novels, but I think that both of these authors are very dark (and exceptionally good at what they do). On the other hand, women like Mo Hayder or Tess Gerritsen or I tend to get a lot of attention when we take on the same issues in the same way. People expect women to be softer, I suppose. The dichotomy is that in most countries, women buy the majority of the books. In the US and UK, for instance, almost 85% of all readers are women. So, we have always been interested in this subject matter. I think it’s about time we started not just writing about it, but bringing the perspective of women to the topic of violence.

It seems more and more common that authors use made up places instead of using cities and places that really exist. Why is that?

I write two different series—one is set in fictional Grant County and the other is in Atlanta, which of course is a real town. I find it much easier to be in Grant because I can make up roads and neighborhoods. I’m always so nervous when I write about Atlanta, even though I’ve lived here more than half my life, because I’m sure I’ll get something wrong and some helpful reader will write a terse letter outlining my mistake. I find it much easier to be in a completely fictional world, as I’m sure most writers do!

Is there a difference in what kind of stories would work great in the US, contrary to what would suit the Asian or European readers?

I think that a good story is universal. I am, of course, grateful that I have extremely diligent translators for my work in various countries, but despite what Hollywood shows the world, there are more things Americans have in common with the rest of the world than things that set us apart. For instance, most Americans live in small towns. We don’t all inhabit New York and Los Angeles. Most Europeans live in small towns, too. I also think that as human beings, we all have a natural curiosity about violence. It’s in our DNA to note danger, whether we’re slowing down to look at a car accident or reading a gripping thriller late at night. Our brains are constantly learning from experiences, and there’s no safer way to experience a good thrill than in a well-crafted story.

Are you familiar with any of our Swedish crime authors?

Well, of course Stieg Larsson is well known here as well as Henning Mankell. Liza Marklund is absolutely fabulous and I eagerly await her next work. Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to get novels translated into English. The US and UK publish around 250,000 books each every year. There’s not a lot of room for other authors. I do enjoy many Scandinavian authors. Karin Fossum is an excellent storyteller and Peter Hoeg wrote one of my favorite stories.

How much of the time to produce a book is research and how much time is actual writing?

Usually it takes a year to complete a book, but I’m often doing research and making notes for two or three books at a time. Since I’m writing a series, there are some things that I think of about my characters that don’t quite fit in the current book but will work really well in the next. So, I’m always taking notes and marking articles that I think might be relevant to the next book.

You use really nasty crimes in your stories, why? Is it possibly to create a debate?

I think crime novels have always been at the center of debate because there is a certain immediacy inherent in the genre. Jim Burke wrote a wonderful novel (The Tin Roof Blowdown) about New Orleans after Katrina—it was angry and political and a damn good read; all the things that good crime novels are. He was able to write about a wound in America’s psyche that was still raw because he’s a good crime writer. He didn’t waste time staring at his belly button like so-called “literary” authors do. He sat down and wrote a story.

Not many authors write two “series” parallell, but you do. Is there an agenda behind this, or is it just for fun, to avoiv getting bored with your characters…?

I love writing, and I love taking chances with my work. When I wrote Triptych, it was because I had a story that wouldn’t quite work in Grant County. It opens with a prostitute being murdered, and we don’t really have those in Heartsdale—well, maybe we do, but no one really talks about them. I needed the anonymity of a big city, and Atlanta, my home, seemed like a good setting. Once I started writing about Will Trent, I couldn’t stop. I knew there were more stories to tell about him and so I decided there would be a second series.

Are there real people behind the characters in your stories?

I’m sure I’ve taken some people from my real life and put them in my books, but I’m never conscious of it. I think that every writer is a product of circumstance, so there is an eventual blending of real life and fiction.

How come you have written the books in the Grant County series in one order, but in hindsight I would have liked to read them in another?

I think that starting with Indelible is a good idea because it gives you a glimpse of things to come, and explains the genesis of Jeffrey and Sara’s relationship. Of course, as a reader, I am a stickler and I like to read everything in the order in which the author wrote, so perhaps there are people like me who, when they find a new author, start from the beginning and don’t stop until they’ve caught up.

A couple of your books have different names in different countries. This is nuisance when you travel a lot and buy most of your books at airports all over the world. Not only different covers, which is a hustle, but now different names? Why?

I leave the titles up to the individual countries. Generally the English versions all have the same title, but there have been two instances (with Skin Privilege/Beyond Reach and the upcoming Genesis/Undone) where because of market forces or another author having a book out already by the same title, we’ve had to change them. I’ve approved the title changes in both cases. Of course, in non-English countries they tend to change the titles more drastically. Since English is the only language I speak, I think it’s best to leave it to the experts!

What are you working on right now?

I’ve just finished Undone, the next book in Will Trent’s world, and I’m working on Broken, which takes us back to Grant County. A lot of things have changed over the course of the series and it’s been fun writing about Lena again.

If you were to suggest who we should interview next, who would this be, and what question would you ask this person if you could?

I would suggest Mo Hayder because she’s one of my favorite authors. What I would ask her is “Why aren’t you writing faster?” I’m dying for a good book from her.

By the way, did you change your last name, or is it a coincidence…

It’s a coincidence. I was teased mercilessly as a child, so I think I’ve earned the right!

Many thanks for you time and see you at the Gothenburg Book Fair!

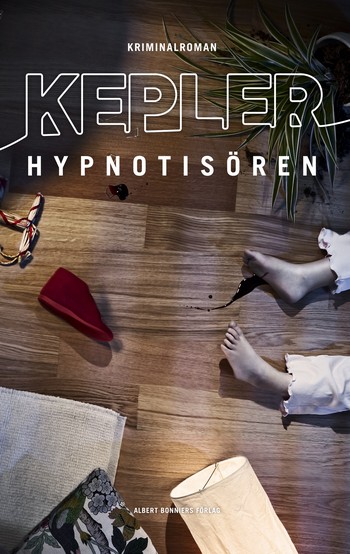

Erik Maria Bark bryter sitt gamla löfte att aldrig mer hypnotisera. Varför? För att han är lika övertygad som Kommissarie Joona Linna om att de brutala morden på en alldeles vanlig familj kan lösas, och den försvunna systern räddas, om bara minnen i det undermedvetna hos den överlevande sonen kan grävas fram. Men var det rätt väg? Har den räcka vidrigheter som följer i hypnosens fotspår kunnat undvikas? Var det Eriks fel, det som sedan hände?

Erik Maria Bark bryter sitt gamla löfte att aldrig mer hypnotisera. Varför? För att han är lika övertygad som Kommissarie Joona Linna om att de brutala morden på en alldeles vanlig familj kan lösas, och den försvunna systern räddas, om bara minnen i det undermedvetna hos den överlevande sonen kan grävas fram. Men var det rätt väg? Har den räcka vidrigheter som följer i hypnosens fotspår kunnat undvikas? Var det Eriks fel, det som sedan hände?

Dan Browns ”The Lost Symbol” låg och väntade på mig när jag kom hem igår 🙂 Har precis påbörjat ”Lord of Chaos” (6:e boken i The Wheel of Time av Robert Jordan) men för detta är det klart värt att göra ett litet uppehåll i fantasyserien!

Dan Browns ”The Lost Symbol” låg och väntade på mig när jag kom hem igår 🙂 Har precis påbörjat ”Lord of Chaos” (6:e boken i The Wheel of Time av Robert Jordan) men för detta är det klart värt att göra ett litet uppehåll i fantasyserien!

Smärtans jungfru är en engelsk polisroman som utspelar sig i sydvästra delarna av London. Detta är den andra romanen med kriminalinspektör Mark Tartaglia i huvudrollen. (Första boken heter Dö med mig och kom ut förra året)

Smärtans jungfru är en engelsk polisroman som utspelar sig i sydvästra delarna av London. Detta är den andra romanen med kriminalinspektör Mark Tartaglia i huvudrollen. (Första boken heter Dö med mig och kom ut förra året)